Mesolithic

Binhamy is known today for the remains of the Medieval moated manor house, but this location nestling as it does on the high ground above the river Neet estuary, has been a favoured spot from the earliest of times. It as if the Norman, Blanchminster family, who built a moated manor house here in the thirteenth century, knew it was a well loved settlement when they called their new home “Bien Amié ”, which can be translated from French as well loved.

It is with this in mind that we must travel 6000 years into the past when the first peoples settled here during their hunting forays. These were the people of the Mesolithic period.

The Mesolithic spans a considerable 6000 years of pre-history from around 10,000 BC to 4000 BC. However, it is probable that these hunter-gatherers did not settle here until towards the end of this period. Early groups entered eastern Britain crossing the land bridge across the North Sea. The peoples who frequented our coast were probably fisher folk who navigated their way across the expanding English Channel. They were interested in the mix of coastal dwelling, with ventures into higher ground areas on our local moors following the game in summer time.

The earliest evidence for these people on the western shores of Britain centre around western Scotland and Northern Ireland and date to around 8,500 BC to 7,500 BC. This is probably because at that early post-glacial date we did not have a shoreline as we know it today; sea levels locally were still much lower than in Scotland. Towards the end of the Mesolithic sea levels had risen and our coastline would not be dissimilar to that of today. It is now that we start to find traces of Mesolithic activity. At Crooklets Beach, Bude and all along our coast we find evidence of their hunting activity in the form of flint assemblages.

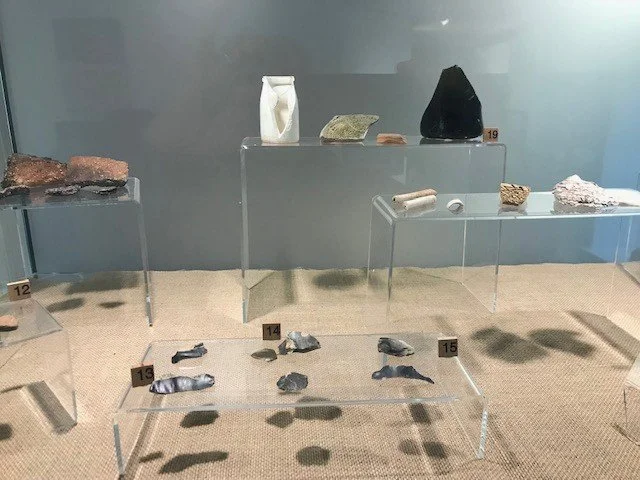

And, at Binhamy, flint assemblages (shown) were found during research carried out by A.C Archaeologists in 2019, suggestions settlement here during the latter stages of the Mesolithic. In fact, much of the pre-history story at Binhamy is derived from the work undertaken by A.C. Archaeology, and they have kindly given permission to use their findings and images in our Binamy story.

Although, these were isolated communities, they did interact with other groups. They traded flint and stones and other valued items with groups from North and East Devon and all along the south coast of England. Towards the close of the Mesolithic, a settlement in southern Ireland even has evidence of goods from Brittany and the suggestion of domesticated cows. This is not so surprising as it may seen. After 6000 years of experience it is perfectly understandable that animals will have been domesticated to the advantage of the group.

Image courtesy of A.C. Archaeology, Exeter

The question of settlement during the Mesolithic is a debated subject. They lived in simple tent-like structures which has left little in the way of footprint. The structures were, nevertheless, quite substantial, perhaps 4 to 5 metres in diameter and the floors may have been sunken into the top soil. It is known that they travelled onto Bodmin moor in the summertime as their flint workings have been found by Dozmary Pool. They may well have returned to the site at Binhamy during the winter; successively, over generations using the same site and reworking the old dwellings.

Modern diagnostic techniques and studies are making this a fast changing subject area and it would be unwise to be too dogmatic about the extent and duration of settlement here, but that they were here towards the end of the Mesolithic is not disputed.

The image is taken from Caradoc Peters’ excellent book entitled, “The Archaeology of Cornwall”.

We now turn to our next period of settlement at Binhamy during the Neolithic - the age of farming and pastoralism.

Neolithic

The Neolithic is an important period for our region as we have some of the best heritage of this age to be found anywhere in England, mainly on our local moors. But equally, we can be sure these people had a base here locally and certainly at Binhamy, where evidence of their presence was identified during the archaeological studies of 2019.

The Neolithic spans a 1500-year period from around 4000 BC to 2500 BC, the start of the Bronze Age. The Neolithic represents the transition from hunter-gatherer to farming, although some will argue that changed to pastoralism as the period responded to different pressures and ideas. It also represents the period when the peoples started to congregate and gather communally and celebrate their ancestors with the construction of Portal Dolmen, as at Trethevy Quoit, and tor enclosures, some of which were treated as sacred areas; the ridge along from Rough Tor being one such enclosure, which also had an elaborate sacred approach path on the western slopes of the Tor.

(Image shows the sacred procession way leading up from the car park at Rough Tor and below, the Portal Dolmen at Trethevy, near St Cleer.)

At Trethevy, the bones of the revered ancestors were removed and placed amongst the group to be part of the festivities. This is not so unusual as it may seem; there are example of later burials that have a pipe down to the ancestor so that food and wine can be poured down for the deceased to enjoy!

Very early in the period- 4000 to 3800 BC - the people lived communally in large halls, often evidenced by a long rectangular series of posthole found on settlement sites. Later, as the culture became more established- 3800 to 3400 BC -families moved out to form settlements of their own or they may have developed pastoralism, roaming with their cattle. If this life-model is accepted, they may have returned to Binhamy on a seasonal basis. These people depended heavily on their cattle for milk and meat- less so for wild animals. However, foraging in woodland for nuts and root crops continued to form an important part of their diet and the high moors were used for grazing their animals during the summer months and for celebrations. Strange as it may seem, they may not have made use of the produce of the sea and shoreline, as was first thought, but the winter here offered the comparative warm of the Gulf Stream warmed Atlantic.

(Image shows the posthole features found on the coast of Scotland and appearing in Brry Cunliffe’s book, “Britain Begins”.)

At Binhamy the settlement probably falls within this “developed” time period. The exact nature of the settlement at Binhamy was not determined during the research with any certainty. For example, one of the areas studied revealed an arc of seven postholes, which were interpreted as being part of a windbreak structure. If correct, it may suggest temporary settlement at times. It is known that these people spent some time on the moors in summertime, perhaps returning to Bude in the winter. But equally, there were other postholes and pits discovered, which may tell a different story. One pit was closed off by a slab of local rock under which were human bone fragments from an earlier cremation. This is rare, if not unique, for Cornwall and may represent the veneration of an ancestor by saving a vestige of the cremated person and entomb the remains beneath the floor of a home.

Research is presently being undertaken by one of the Trustees during 2026 that may throw more light on this period and this may explain some of the above findings.

(The image shows the curved slab found at Binhamy under which were the vestiges of the cremated person.)

Photo. A.C. Archaeology.

The image shows early Neolithic activity at the Neet estuary mouth which would represent at least the winter activity when the group would want to capitalise on the produce of the sea and seashore. During later Neolithic periods cultural belief systems may well have moved away from eating other than their own bread animals. This is because they believed the soul of their ancestors may have been taken up by the wild animals and sea creatures and killing these animals may have created ancestral spirit revenge Their dead were sometimes cremated, others left out to be excarnated by wild animals or deposited in rivers or the sea. Some bones of their dead were collected and entombed and this may account for some of the finds at Binhamy.

At this time sea levels would still be a little below those of today.

The bones were part of the cranium and had been removed from the pyre towards the end of the cremation ceremony. Unfortunately, there were no jaw bones or teeth. If there had been, it would have been possible to sex the individual, check his/her DNA and determine where the individual had grown up as a child. If the bones had not been cremated, it may also have been possible to determine the possible cause of death as the DNA of the pathogen would also be present. It is the skill of modern archaeological diagnostics that is making the coming years so exciting for our local history. It was, nevertheless, possible to radio-carbon date the bone fragments to c3706 to 3641 BC; this falls within that “developed” stage mentioned earlier.

Within the site of Binhamy there is then little in the way of finds until the middle of the Bronze Age.

This remain something of a mystery that may yet be resolved by further studies. But there are some studies which speak of a decline in population levels towards the end of the Neolithic, which could be due to disease (the Plague) caused by pathogen cross-over from close living with animals. Research is presently underway by the Crick Institute that may give answers to this question.

Towards the end of the Neolithic, burials of important members of society, or even of a complete house, were entombed under a long barrow, such as to be found at Woolley, just to the north of Kilkhampton.

(The image shows the enormous Neolithic Long Barrow at Woolley)

Bronze Age

It is ironic that the Bronze Age has left us with numerous burial barrows along our cliffs and within the countryside, but little evidence of early settlements. This is the case at Binhamy, where evidence of settlements were discovered during the research carried out in 2019.

The Bronze Age spans the period 2400 to 800 BC and is often divided into Early Bronze Age (2500 – 1500 BC) Middle Bronze Age 1500-1100 BC and Late Bronze Age (1100 – 700 BC).

The transition from the previous Neolithic farming practices seems to have hit problems with population declines. Towards the end of the Neolithic, the Bell-Beaker folk came to England either filling that population vacuum or maybe even being driven by the consequences of post-Neolithic problems. These Bell-Beaker people used copper artefacts and adorned their lives with gold objects, and they appear to have been searching our Moorland streams for copper and gold when they discovered vast and easy sources of tin.

Tin deposits were rare in Europe, and this drove Bronze Age development and placed Cornwall and Devon at the forefront of this development. The question is, did this disrupt the cohesion of society at this time, which affected Early Bronze Age settlement? We may get the answer to this in the coming years.

So it is that most settlement in Cornwall date from the Middle Bronze Age. Locally we have important settlements at Trevalga, Trevisker and Trethellan and we now know there was a similar settlement at Binhamy. But there would have been many more settlements, now lost to development or buried under sand inundation, as was the case at Trethellan. Tin would have been blended with copper at these settlements by specialist metalworkers, that was the great benefit of the stream sourced ingots; they were easy to process. Of course, there was significant development and tin streaming during the middle Bronze Age on Bodmin Moor and evidence of settlements there can still be seen today.

At Binhamy, A C Archaeology found a cluster of postholes and pits of this period indicative of settlement. But this remained an active development site in subsequent eras, and much will have been destroyed.

(Image by A C Archaeology)

Also, found at Binhamy were pieces of the ubiquitous Trevisker Pottery Ware. This was widely used throughout Cornwall and beyond from the Neolithic through to the Romano-British periods; the latter period pots, incidentally, may be identified by grass imprinted on the fabric giving the name Grass-Ware.

The fabric of the Binhamy pottery date to the Mid-Bronze age and contain all the minerals that relate to the Gabbroic clays of the Lizard. There were five sites at the Lizard from which clays were sourced, and the archaeologist Dr Imogen Wood has studied the minerals within these clays and can determine which of the five areas they came from by analysing the mix of minerals within the fabric and their weathered form.

Dr Wood does postulate that the Middle Bronze Age people could have used other similar clays sources nearer to their own locality but instead chose to use at least some of the Gabbroic clays and mixed this with their own local clay for societal cohesion reasons. Similar group loyalties were also evident in the Neolithic.

The pots were not made at the Lizard, incidentally; it was the clay material that was sought and presumably exchanged for other locally produced goods.

It was originally assumed that the hard Gabbroic clays better resisted the heat of cooking processes but the societal cohesion theory is now preferred. Incidentally, the pot found at Binhamy is thought to have been a storage jar and would not have been subjected to the heat of cooking processes.

The A C Archaeology drawing shows the classic chevron pattern often included with these pots and this can also be seen on the actual pot sherd above.

Just to expand on the societal implications of sourcing of Lizard Gabro clays; could the large community gathering of these times, which took place on our moorland, with exchange of goods, inter-leader gifts and inter-community trade, all be part of giving the Bronze Age people a sense of common identity and societal bonding?

A interesting footnote to this is that with the coming of the Normans, local people were obliged to buy their pottery from specialised shop outlets and individual small communities lost the skill to produce their own pottery.

It is equally ironic that despite these apparent efforts to create cohesion, the Bronze Age ended with societal collapse, possibly due to environmental factors, maybe made worse by volcanic activity and consequential disease brought on by the movement of vermin spreading early forms of plague. Research is presently ongoing to answer these questions too. But this had consequences within societies at the start of the Iron Age as communities were forced to find settlements at lower elevations, particularly off Bodmin Moor.

Iron Age

We are surrounded in our area with evidence of Late Iron Age settlement- usually in the form of Cornish Rounds or defended settlements. The image shown is of Stamford Hill. But we also have three very large so-called forts at Clovelly Dykes, Warbstow and Castle-an-Dinas. These were more involved in trade, celebration or animal husbandry forming part of transhumance of animals on to and off the moorland for summer grazing rather than a defended fortress. Although, at Clovelly Dykes there is evidence of fighting during the early Iron Age, possibly reflecting the unsettled nature of society following the Bronze Age collapse and consequential resettlements to lower elevations.

At Binhamy, we do not appear to have had an enclosed or defended settlement, but we do have evidence of settlement in the form a typical Iron Age house which was revealed by a ring ditch or gulley and postholes. The ring gulley was 16.5 metres diameter which is typical of a large chieftains Iron Age house.

(Images again from A C Archaeology research 2019.)

The green section on the lower image is post-medieval and this is the problem as the site has been occupied over so many periods of pre and early history.

This photo may be a better representation of the settlement at Binhamy. This was taken at Castell Henllys Iron Age village, near Eglwyswrw, Pembrokeshire, South Wales. The chieftain’s house here was 15.5 metres internal diameter.

Note: no chimneys; the smoke was allowed to slowly drift up through the thatch. A strong up-draft would carry flames or hot ash with it, which could set the thatch alight.

We can imagine that with the arrival of the Romans, a Romano-British settlement will have developed here. Houses of this type with ring gulleys- sometimes called drip gulleys were a feature during Roman-British times.

It may be pushing ideas too far, but it is known that there were salt making facilities along the Neet estuary and at Widemouth Bay in Roman times; it is quite possible that this hamlet may well have had a role in that activity.

Saxon Age

During the Saxon age, Binhamy would almost certainly have been a busy place. We cannot know whether this would comprise one or more families. Early maps do show vestiges of strip fields. Studies done recently (2025) at Tresibbet, near Jamaica Inn, Bodmin Moor, comprised a small hamlet of two or three families each owning individual strip fields, out houses, animals and various ricks of winter forage and bedding, but sharing certain animals, such as a bull. This is a possible model for what existed at Binhamy.

Unfortunately, with the arrival of the Normans and eventually the Blanchminster family, Binhamy will have taken on a very different character and much of the Saxon family element will have been developed out.

Since writing the prehistory summaries above, A C Archaeology have kindly forwarded many of the above mentioned artefact on loan to the Heritage Centre at the Castle, Bude and Janine King, the Heritage Curator, has put together a beautiful display of the artefacts for the public to see. She will be adding other material to the display over time, but the material already on display demonstrates the 10,000 year heritage of Binhamy and the land around the site.

It is worth a special visit to see the skill of the flint work, apart from the other material.